Retrospective on Catalyst, a 100-person biosecurity summit

You can also read this post on the EA forum. This post was written by Tessa Alexanian, Megan Crawford, myself, Finan Adamson, Brian Wang, and Cody Wild.

This is a retrospective on Catalyst, a one-day collaborative biosecurity summit that was held in February 2020 in the San Francisco Bay Area, written by the organizers 1 for anyone who might run a similar event in the future.

tl;dr

- It is possible for a small group of volunteers to run a high-quality conference without making it any of their full-time jobs, but give yourself 8 to 10 months to bring an event of this scale from concept to execution. (See: Timeline.)

- Define the outcomes you want from your event early on. This will shape so many decisions, from contacting advisors to choosing a venue. Check out Gather for a good step-by-step guide. That said, measuring outcomes is really hard!

- There is an unmet need for non-hierarchical and connection-focused conferences. We prioritized discussion, shared problem-solving, and networking between participants, and, from the feedback we received, we think these efforts contributed to more dynamic conversations and a stronger sense of community. (See: How did the event go? and Programming and Event Structure).

- Experienced advisors are great. You don’t need a lot of their time to get huge benefits; a few 1-hour meetings and permission to put their names on the website was enough (see: Getting help and mentorship).

- If you have funding for the conference you should try to understand the tax implications before starting to spend money. This worked out fine for us, but could easily not have (see: Budget).

- Leave slack in your budget, timeline, and day-of program. We made incorrect predictions about how long things would take (especially booking speakers and finding a venue) and about how much things would cost (especially catering). (See: Timeline and Expected vs Actual Budget, which we hope will help future organizers to make better predictions).

How did the event go?

We ran Catalyst because we wanted to create a venue for discussing biosecurity in the SF Bay Area. The theme of the summit was that biotechnology is advancing quickly, many different futures seem possible, and that we must thoughtfully collaborate in order to ensure that we get a positive future.

Catalyst was attended by about 100 people representing various levels of engagement with biosecurity (from undergrads to experienced biosecurity professionals) across several different communities (effective altruists, biohackers, academics, industrial biotechnologists, and policymakers), with a slight preference for those coming from the SF Bay Area in order to facilitate continued post-Catalyst momentum. The event was funded by a grant from the Long Term Future Fund.

Outcomes from the day of the summit

We did an immediate post-event survey to gather outcomes from the event. We intended to run an additional six-month follow-up survey, but then 2020 happened.

We don’t feel totally satisfied with the robustness of our outcome data, but also aren’t sure what a solid methodology for assessing event impact would have been. Participants seem to have considered the event a good use of their time; when asked if they would attend a similar event in SF again, 30/35 respondents said “Yes”, and the remainder said “Maybe”. One experienced organizer told us that Net Promoter Score was a standard assessment: our NPS was 742 but to be honest we’re not sure if that’s a good score or not. (Edited to add: according to a comment from Ben West this is quite a good score.)

In both the survey and while talking to participants, we heard that Catalyst exceeded expectations. Many people shared enthusiastic positive feedback with organizers during the reception, and the energy in the room was very high. Participants appreciated how small the summit was, how many cool people were there, the exciting conversations, and the diverse backgrounds of attendees and speakers. Some illustrative quotes:

- Beth Vitalis: “It is amazing how much happened in one day. You had us do more than talk about ideas, we actually demonstrated that we can work together to solve the challenges.”

- Linch Zhang: “It seems really good to have more conferences like this, where there’s a shared interest but everybody comes from different fields so it’s less obviously hierarchical.”

A few more concrete outcomes, each reported by a different participant:

- Became 10% more likely to apply to work on biosecurity research ideas at an EA organization

- Connected with FBI WMD officers (who were hosting a session) and received offers of help from them

- Became closer with other biosecurity researchers at their institution as a result of their shared summit experience

- Learned of subjectively exciting incentives for medical countermeasure development that they hadn’t yet heard about

Additional outcomes

The main outcome of Catalyst was the day-of experience for the participants. A few secondary outcomes:

- The day’s shared experience has been a useful point of connection for later networking; several organizers have connected contacts with a note along the lines of “…and you were both at Catalyst!”

- The organizing team feels very positively about the project in terms of the skills they built, connections they made, and mentorship they received.

- We shared slides and photos from the event on our website; we have some other documentation (e.g. group brainstorming notes) that we’re less sure how to use.

We were hoping to have more post-event outcomes, but several difficult-to-anticipate things got in the way of this:

- Our A/V contractor somehow deleted their audio tracks, so we had no recorded talks to share. Maybe we could have prevented this (backup phone recordings?) but the contractors had good reviews and we doubt that level of paranoia was warranted. We considered trying to get speakers to self-record their talks, but in the end just shared some slide decks on our website.

- Two weeks after Catalyst, the SF Bay Area went into shelter-in-place because of the emerging COVID-19 pandemic. This took our attention away from our ideas for follow-up events, connecting participants, or writing up outcomes from problem-solving discussions.

We think a counterfactual version of this event, in which the two things above did not happen, would have had greater impacts beyond the day-of experience of the participants.

Should other people run a similar event?

Basically yes. We think the event provided good value for time and money.

Time: organizing Catalyst was the main side project for several of the volunteer organizers for several months, but it wasn’t a ridiculous amount of work. A rough estimate is that we spent between 350 and 500 hours on the event, split across the 6 organizers. See more details under Organizing Team below.

Money: a much cheaper event could be run either online or with in-kind offers from an academic venue… but we think there’s quite a lot of value in having a nice venue (to put people in a novel, connection-oriented mood) and providing good food and drink (so people stay in the venue and talk with each other). See more details under Budget below.

One reason we might not recommend running a similar event is if your team has only minimal connections in the problem area you’re focused on. We’re not saying you need to be super well connected, but you should hit the threshold of “knows someone who knows someone’s email” for at least some of the speakers you’d want to invite, and having accessible, well-connected advisors is really helpful (see more details under Recruiting Speakers and Getting help and mentorship).

Detailed Notes and Advice

This section is long, and may not be interesting for anyone not trying to organize a similar event! You have been warned. We categorized each section as a success. near miss, or failure.

Timeline

Our timeline was a near miss. That is, nothing went wrong, but if we hadn’t for external reasons needed to reschedule, the event likely would have gone poorly. Our big mistakes were:

- Thinking we could put together an event in only 6 months.

- In retrospect, we needed 8-10 months. Maybe this could have been shorter if the organizers weren’t volunteers, but it’s hard for us to estimate that.

- This error happened in part because we first applied for a grant in December 2018 and didn’t change the timing when we re-applied in April 2019 because we were trying to overlap with the SynBioBeta conference in October 2019.

- Not realizing how many aspects of programming were chained sequentially, and needed to be completed before we could recruit participants.

- The chain went something like: clarify our goals and purpose → so we know which major speakers to invite → so we can confirm some exciting people → so participants will be excited to apply.

- Thinking it would be easier to find a venue that fit our requirements.

- We wanted something larger than an Airbnb or a restaurant, cheaper than a conference center, and more unified than several scattered rooms on a university campus.

- There was no obvious aggregator that allowed us to survey all potential Bay Area venues. Ultimately, we found our venue because one of the organizers had attended an event there.

- See more under Venue, Food and other Logistics.

It’s also a near miss (though one entirely beyond our control) that we’d have cancelled Catalyst if it had been scheduled a one week later. As it was, Catalyst happened 4 days before the first reported community spread of COVID-19 in the USA and 22 days before the SF Bay Area went under a shelter-in-place order. It’s a little weird to have hosted an event on biosecurity and pandemic preparedness in late February 2020, haha??

Full Timeline

2018

- December: First Long Term Future Fund grant rejected

2019

- February: End of CEA Community Building Grant for East Bay Biosecurity; group strategizes about whether we can run an “unconference” with remaining funds

- April: Second Long Term Future Fund grant approved, organizing team assembles to run an event in October

- May: Bi-weekly organizer meetings begin

- August: Family emergency causes us to postpone until February 2020 (in retrospect, 6 months was not enough time, and postponing vastly improved the event)

- September: Walkthroughs and tours of various venues

- September 18: Venue booked

- November 12: First-round applications open

- December 7: First-round applications close (73 total applicants)

- December 12: First-round acceptance decisions sent out (59 Yes, 8 No, 6 Waitlist)

- December 20: Catering booked

2020

- January 15: Open rolling second-round applications (29 additional applicants)

- January 20: AV company booked

- January 31: Venue walkthrough with catering person

- February 8: Furniture rentals booked

- February 18: Closed second-round application (though we accepted a few additional people who emailed us; we had 15 applicants in the final week)

- February 21: Speaker’s Dinner

- February 22: Main event!

Budget

Success in terms of handling available funds, but near miss when it comes to taxes. Organization and a conservative buffer were important to the former. If we could do things again, we’d clarify our tax situation (an individual organizer receiving a multi-thousand dollar grant) earlier on with our funders. Our general budget advice:

- Track your budget with a spreadsheet and a separate debit card.

- We had a detailed budget spreadsheet and put a lot of work into keeping it up to date. This was particularly valuable as small, last-minute expenses mounted in the week or two before the event. This spreadsheet3, combined with the separate event account (point below), made us very confident that we could account for where all our event funds went.

- We acquired a separate checking account and debit card for event funds. This was easier than expected (it took less than 15 minutes), and enabled us not to have to tease apart many months of personal vs. event finances in a personal account.

- Anticipate tax complications

- The organizer who received funds (personally, not as a representative of a legal non-profit) didn’t end up being liable for them as individual income, but this was messy to navigate, and the organizer spent several weeks worried about owing taxes on ~30K of additional “income” that had already been spent on the event.

- Said organizer ended up filing taxes without a lot of personal confidence that the grant was not income, based on the word of a tax accountant saying “yeah, that’s probably fine.” This was stressful!

- If you receive a similar grant in future, we recommend inquiring up-front about the tax categorization of the funds.

- Leave extra funding slack

- About one month before the event, we looked for (and found) an extra source of funds ($2500) to cover travel in case we ran through our main budget with last-minute incidentals (printing, photography, etc.).

- We didn’t end up needing those funds (and eventually returned some money to the LTFF) but it was a good decision to create extra slack in our budget.

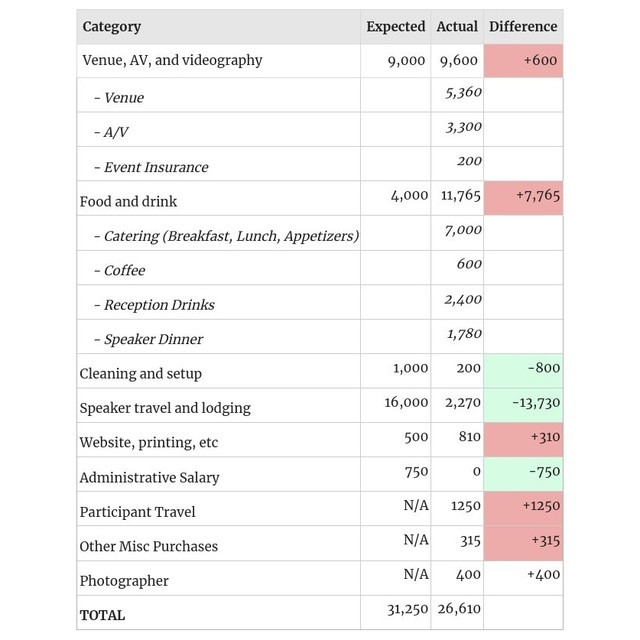

Expected vs Actual Budget

Our original budget was put together with advice from our advisors and other event organizers we knew, but it ended up being incorrect in a few ways.

- The greatest difference is in our speaker travel costs, but that’s because we pivoted intentionally towards more locality after talking to advisors, which meaningfully reduced the cost of speaker travel. We also decided to blur the speaker and participant distinction, meaning half of our speakers were giving lightning talks and we didn’t cover their travel.

- Our estimate of food and drink was way off. Our catering cost alone was 1.75x of our total estimated food and drink budget, even though we worked quite hard to find an affordable option. We ended up spending around $100 per person to provide two meals, coffee, and reception appetizers + drinks. (The food was provided by a caterer and the drinks were an add-on at the venue.)

Programming and Event Structure

Our program and event structure was a success, especially the conversations between individuals. The event had the following kinds of structured programming:

- Long Conversations: Experts had a chain of one-on-one conversations with each other around a central prompt, combining the conversational style of a fireside chat with the viewpoint diversity of a panel. (Format from the Long Now Foundation.)

- Talks and Lightning Talks: Speakers with microphones at the front of a room. You know what a talk is.

- Workshops: Guided, participatory discussions.

- Design Jam: Small-group brainstorming sessions on open problems at the intersection of biotechnology and society. Everyone signed up for (or was assigned) a group ahead of time.

You can see the complete schedule in this PDF. As the schedule PDF shows, we had a few bookable spaces in the venue, but in practice participants just talked informally with each other. Here is our main programming advice:

- Leave generous time for breaks.

- Many participants said the most valuable parts of the event were 1:1 or small group conversations, which mostly happened during breaks.

- Frequent breaks also mean that you’re not scrambling to get different rooms back in sync with each other if speakers go over time. We never had more than 1.5 hours of “sit down and listen” content (talks, workshops, etc.) in a row.

- Organizing small-group problem-solving (like the Design Jam) is a lot of work but worth it.

- This was the part of the event that participants reported finding most valuable after 1:1 conversations.

- Groups were mostly hosted by participants, though we recruited hosts from a few organizations (FBI WMD Program, Innovative Genomics Institute, iGEM).

- A nice thing about having organizations host groups is that you may have a chance to directly influence organizational policy on the problem. That said, our highest-energy group was hosted by a participant4.

- Printed templates helped the groups to structure their design discussions.

- We adapted several templates from Design A Better Business. Not every group used the templates, but we’re glad we had them on hand.

- Ask group hosts to prepare some materials in advance of the event.

- We asked all of our hosts to share 1-page design briefs ahead of time. In the end, neither the briefs nor the design jam groups were finalized until right before the event, but the request helped to ensure hosts were well-prepared, and we printed the briefs and shared them along with the templates.

- Full group report-backs are often boring, but the ones during the Design Jam ended up being fun and engaging, we think because they were very strictly timed (we projected a YouTube video with a 90-second countdown while each group presented).

- Long Conversations are an interesting, but not totally satisfying, format.

- We chose this format because we wanted more viewpoint diversity than is possible with talks or fireside chats, but dislike how large panel conversations are often rushed or shallow.

- Several participants appreciated the attempt to do an interesting format, but others said they would have got more out of moderated discussions.

- Some of the speakers were confused by the format and felt uncertain about how to do it well.

- We sent our speakers lists of questions ahead of time, and printed them out on the day-of, but some of their conversations veered away from our intended topics. Explicitly asking them to interview each other using our prepared questions might have led to better conversations, but we’re note sure.

- People want technical and participatory content (i.e. workshops) but these are hard to recruit for.

- A workshop is a larger ask for presenters than a talk; in the end both of our workshops were hosted by a single person (Tara Kirk Sell, an absolute hero).

- The workshops were really popular, though! The rooms ended up overcrowded, and participants said on the survey that they wanted more of that kind of in-depth content.

- It’s not easy to get participants to initiate semi-formal discussions.

- We invited participants to connect with each other over Slack, and to coordinate unconference-style breakouts via a spreadsheet, but both of these tools were effectively ignored.

- We put discussion prompt cards on every table in the main space, but they were mostly ignored.

- We did find that emailing speakers and asking them to host office hours worked well.

- People want to make new 1:1 connections, but social engineering is hard.

- We had lots of time for unstructured conversations at the event, but several respondents wished there were more opportunities to network in advance of it.

- The Slack instance was basically inactive, though perhaps a platform (e.g. Swapcard) that helps to book 1:1 meetings would have been used?

- We think direct intros facilitated by organizers would have been highly appreciated, but also would have required more deliberate effort.

- We perhaps should have created contexts that nudged people from similar backgrounds/workplaces to spread out. (One survey respondent felt it was clique-ish, but we’re not sure how representative this was.)

- We had lots of time for unstructured conversations at the event, but several respondents wished there were more opportunities to network in advance of it.

Venue, Food and other Logistics

Our conference logistics were a success. We think logistics are really important, since even if a conference goes well intellectually, if it’s chaotic on the day of, or if the food is bad, that can dominate peoples’ experience. We were pleased to have a number of people day-of who came up to the organizers and said they were impressed with how smooth and problem-free the day as a whole was for them.

We think our venue and food were solidly a success, despite a few minor issues. AV was a failure in its outcome, though it’s not necessarily clear what we should have done to prevent that. Onto some more detailed notes:

- Our venue, The Laundry SF, was probably as good as we could get at our price point.

- Many nice 100-person venues only have a single room. It was challenging to find a venue with lots of rooms without escalating up to a full conference center, which was way outside our budget.

- Other venues had bundled costs (cleaning, in-house caterers, etc.) that weren’t obvious until we started emailing them. More than once, we thought a venue would work until we calculated how expensive their required caterers were.

- We wanted somewhere with lots of small spaces, but many of the spaces in The Laundry were somewhat informally divided, and we did have one complaint that sounds easily traveled between rooms.

- Multiple tracks of fully sound-isolated programming probably requires a meaningfully larger venue budget.

- Ensure you have enough day-of slack to make it probable that the day goes smoothly.

- It was useful to have non-organizer volunteers day-of, so that the organizers had more slack to quickly solve problems, rather than having to hold down the fort on straightforward tasks like rearranging chairs or checking people in.

- AV is surprisingly expensive, more than you’d predict from the prices of individual components.

- The lowest price we could find for renting a projector, a screen, two microphones, amp, and a videographer for the day was $3300. Hiring a technician increased costs significantly, in part because companies that offer technician services also charge more for equipment rentals.

- There is also some probability of catastrophic error even if you hire a well-reviewed professional (in our case, having our audio track accidentally deleted) though it’s hard to get a calibrated estimate of this from our single experience.

- It’s better to book speaker travel on individual airlines than to use Expedia.

- Expedia makes it super difficult to make any modifications to a reservation (even just changing a mistaken passport country) unless you are the person whose name is on the booking.

- Catering is expensive, but it adds a lot to participants’ experience to have food available throughout the day.

- Many venues will make you use expensive onsite caterers; one reason The Laundry was within-budget is that they allowed us to bring in a separate caterer.

- After contacting many people, we chose a caterer who was accommodating and responded quickly, which ended up being a one-person operation rather than a more formal business.

- We asked about food preferences in a participant survey and took that into account in our food choices, mostly by leaning into having lots of options.

- We didn’t realize we’d need a catering prep space in the venue; we triaged this day-of by converting a discussion room into prep space, but we probably should have explicitly allocated space for that ahead of time.

Recruiting Speakers

We’re really happy with the group of people who ended up speaking at Catalyst (success) but we had a near miss with cancellations (almost 20% of our invited speakers had to cancel somewhat last minute). Thankfully, we had a lot of flexibility in both our venue and schedule.

When deciding who to invite, we thought about the balance of perspectives we wanted (e.g. covering industry and academia, ideally local) and specific topics we wanted to cover. Our advisors were extremely helpful at this stage, as they often knew of good speakers who would provide desired perspectives. We also made a long list of relevant organizations (mostly local ones) and looked up people who worked at those organizations to contact.

Some additional advice on recruiting speakers:

- To attract speakers, answer: why should they spend a work day at your event?

- One advisor suggested that, when deciding how to respond to an invitation, people will check (roughly in order): the event’s title, the date, who else is coming, the blurb, the host organization, and whether it’s in a cool venue or location.

- Following from this, it’s really useful to have high-profile advisors on your website. Some people we contacted reached out directly to advisors to check that we were legit.

- Get warm introductions whenever possible. Our advisors often had contact information for the people they recommended, so we could send something like “our advisor, [COOL PERSON], thought you’d be a great fit for the event because [REASON]”.

- When sending cold emails, be brief, make sure it sounds like a cool opportunity (our default subject line was “Spark collaborative biosecurity discussions at Catalyst - February 22, 2020”) and include a small paragraph about why they’d be a great fit (“your work on X would really fit in with the event because Y”)

- One advisor suggested that, when deciding how to respond to an invitation, people will check (roughly in order): the event’s title, the date, who else is coming, the blurb, the host organization, and whether it’s in a cool venue or location.

- Plan for some speakers to cancel.

- Of the 19 invited speakers who we ever had “confirmed”, 4 of them didn’t end up presenting at Catalyst through a combination of illness, competing events, and life emergencies.

- This ended up being fine because we moved a bunch of our lightning speakers around. and left one room mostly empty throughout the day.

- Recruit some speakers from event applicants.

- We asked people if they were interested in giving lighting talks when they applied to Catalyst. This helped to identify highly-engaged applicants and resulted in some excellent talks.

- Host a speaker dinner the night before the event.

- Our speaker dinner cost ~$1,800, and gave everyone a chance to meet ahead of the event, which was especially valuable for the long conversation speakers. It was also an excellent bonus networking opportunity for the most engaged participants.

- We should have given people a fixed date by which to RSVP, and made it clear whether we allowed +1s at the dinner (neither of these really created problems, since the unanticipated +1s just ate the food from the people who didn’t show up, but… near miss).

Recruiting and Communicating with Participants

Overall, we feel happy with the participants who were present at Catalyst (success) and no one seemed terribly confused by our communications (success?). We sent a lot of emails in the few weeks leading up to the summit, with various actions for participants to take, and that seemed like a good way to build enthusiasm / engagement.

- High-engagement events should probably have an application and multiple applications rounds.

- We liked our system of running an initial round of applications that closed two months before the event, followed by rolling applications until a few days beforehand.

- Seeing the applicants in the initial round closed allowed us to do targeted outreach to increase the diversity of participants.

- The application deliberately set a participatory tone, asking whether applicants would be interested in giving talks, moderating discussions, or preparing problem statements for collaborative brainstorming; we used this to recruit people to give lightning talks and host design jam groups.

- We liked our system of running an initial round of applications that closed two months before the event, followed by rolling applications until a few days beforehand.

- Reviewing applications required ~10 hours and careful information management.

- Each application was reviewed by two organizers. In separate tabs of a Google Sheet, they rated applications from 1 to 5 and noted down demographic data (e.g. “early career”, “DIY bio”). We accepted everyone with a high average rating, then had a long meeting to make decisions about marginal applicants (e.g. those with an average rating between 2.5 and 4).

- We tried a complex anonymization process, messed up the name <> key mapping, and wasted a lot of time. We should have just hidden the identifying columns in the Google Sheet.

- Try to make it financially easy for people to participate in the event.

- We originally thought we’d charge a small ticket price, but decided that didn’t really serve our community-building purpose, and it seemed like the application process provided sufficient indication that participants would be engaged.

- We were inspired to ask if participants wanted travel financing after seeing the Global Community Biosummit application; in the end, not too many people used this, but we’re glad we included it.

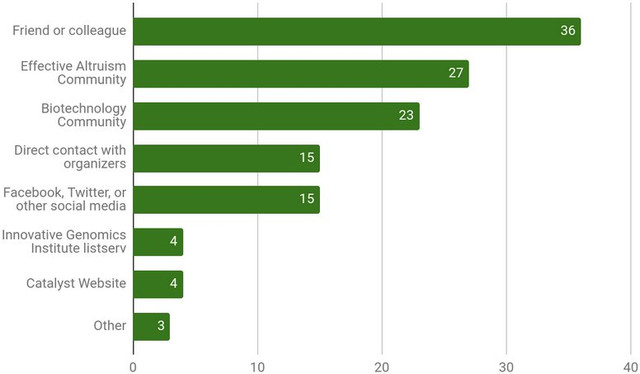

- Participants mostly found out about the event through word of mouth.

- Here are the answers to “How did you hear about Catalyst? (select all that apply)”. Responses are from 81/85 first-round applicants.

- These answers might look different from the second round, where we did a bit more direct outreach. They might also look different if we knew anything about marketing, but we did and do not!

- Emails sent through any kind of newsletter service often go to spam.

- We were surprised by this; we had a mild crisis when we realized many people weren’t getting the emails we were trying to send via Mailchimp.

- In the end, we used a shared Gmail account and split all speakers, participants, organizers, and volunteers into Google Contacts lists, so it was easy to BCC everyone from a particular group at once. (Always double-check that you’re sending BCC if you’re doing things this way.)

Organizing Team

Catalyst was organized by a team of six people (Tessa Alexanian, Cody Wild, Finan Adamson, Jeffrey Ladish, Megan Crawford, and Brian Wang), helped by three advisors (Megan Palmer, Kevin Esvelt, and Jun Axup). We estimate that we spent between 350 and 500 hours organizing the event, split unevenly across the six organizers.5

This team grew around a core set of existing organizers of the East Bay Biosecurity meetup. All organizers on the team had some level of event organization or operations experience, including:

- High-level volunteer leadership positions at EA Global

- Running operations for a small non-profit organization

- Leadership positions running large (80+ person) community social events

While we don’t have a clear counterfactual, we believe this experience was valuable to the execution of Catalyst, both in the form of practical logistics (e.g. having some notion of how to book a venue) and in terms of judgment and intuitions honed from prior similar situations.

Getting help and mentorship

Our advisors were super important, even though we only had a few meetings with them (maybe 5 hours in total).

- They gave us a ton of useful speaker recommendations, and connected us with experts who gave us extremely useful and targeted advice (e.g. a 10-minute phone call with Lisa Solomon about the Design Jam activity, which was so dense with ideas that it kind of reset Tessa’s concept for how useful a consultant can be).

- Having a list of advisors on the website helped us to build credibility and recruit speakers / participants. Some people we contacted reached out directly to advisors to check that we were legit.

We also had a really helpful 30-minute call with a CEA staff member early on about logistics and programming, which covered lots of useful ground (e.g. how to structure emails to speakers to increase the chance they’ll be interested).

Managing meetings and information

We have some additional advice specifically around meeting and information management:

- Regular team meetings are critical for getting work done / maintaining momentum.

- Do not end your meeting without a clear list of action items, each of which is assigned to a specific person and has a specific deadline (by default, “the next meeting”).

- Take detailed meeting notes that are listed under dated meeting sections.

- Immediately after a meeting, send out a scheduling poll for the next meeting (via Doodle or when2meet) so as to minimize the possibility of losing momentum.

- You don’t necessarily need to add new communication tools to your life.

- The organizers tracked work and communicated via Google Drive and Messenger, which we all already used regularly. We experimented with Slack and Asana, but stopped since they were adding complexity without much additional value.

- Status tracking of speakers and participants in spreadsheets was especially helpful. (We joked that This Conference Was Brought To You By Google Drive.)

- One organizer perspective: We did a pretty good job staying organized, but there were some cases where it would have been nice to have some more clarity and who had been contacted about what and what remained to communicate to them. I could imagine a name of invitee with a bunch of checkboxes in columns past the name.

- Create a shared email that all organizers can log into.

- This meant that communications to most speakers weren’t strictly bottlenecked on one person, even if they were a primary contact.

- It also connected access to other centralized accounts via e.g. 2-step verification.

- In addition to assigning action items, define areas of responsibility.

- We did this in the last six weeks of organizing, but think it would have been useful to have more well-defined areas of responsibility earlier, in the explicit form of “it is this person’s job to do X”.

- Explicit responsibility to track a specific area would mean that a single person could have clearly reported on “the status of speakers is X”, rather than us assembling that big-picture status during long, granular meetings

Other Resources

- Gather: the art and science of effective conventing. (Seriously, this is so good. It’s like a worksheet on effective events. We only discovered it a few weeks before Catalyst and that’s a crying shame.)

- EAGxNordics 2019 Postmortem

- EAGx Boston 2018 Postmortem

- EAGxBerkeley 2016 Retrospective

-

Most of the text was written by Tessa Alexanian and Cody Wild, with substantial input and review from Finan Adamson, Jeffrey Ladish, Megan Crawford, and Brian Wang. Thanks also to Aaron Gertler for providing feedback on a draft.

-

To find this score, we asked “How likely are you to recommend (a similar event to) Catalyst to a friend, on a scale of 1-10?”, then took the ((# of 9 to 10 ratings) - (# 0 to 6 ratings)) / (total responses) = (27 - 1) / 35 = 74.

-

For anyone curious, here is the exact budget spreadsheet we used. It probably won’t be comprehensible to non-organizers, but should demonstrate the level of detail.

-

It was, ironically, focused on non-pharmaceutical interventions for pandemics… 4 days before the first reported case of community spread of COVID-19 in the USA.

-

Tessa estimated (based on detailed personal time tracking) that she spent 10-15 hours per month while actively working on the event (May-July 2019, November 2019 - January 2020), 65 hours in the three weeks immediately before the event, and a little over 12 hours on the day of the event itself. (She more or less took a break from August - October 2019 due to a family emergency, and estimates about 3 hours / month of work during that time.) Two other organizers estimated their time as a rough multiple of this, as “between 0.75 and 0.9 the amount of time Tessa spent” and “maybe 0.4 x Tessa’s estimate”.