Does the US nuclear policy still target cities?

The history of nuclear strategic bombing

Daniel Ellsberg’s The Doomsday Machine brought my attention to a horrifying fact about early US nuclear targeting policy. In 1961, the US had only one nuclear war plan, and it called for the destruction of every major Soviet city and military target. That is not surprising. However, the plan also called for the destruction of every major Chinese city and military target, even if China had not provoked the United States. In other words, the US nuclear war plan called for the destruction of the major population centers of the most populous country in the world, even in circumstances where that country had not attacked the United States or its allies. Ellsberg points out that at the time, people at RAND and presumably other parts of the US defense establishment understood that the Chinese and the Soviets were beginning to diverge in strategic interests and thus should not be treated as one bloc. Nevertheless, the top levels of the US command, including President Eisenhower, were committed to the utter destruction of both Chinese and Soviet targets in the event of a war with either country.

The policy of destroying cities is a legacy left over from strategic bombing in World War II. The destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki are the most famous, but the fire bombings of Japanese and Germany cities destroyed far more infrastructure and killed far more people than the two atomic bombs. The given rational for strategic bombing was to destroy the ability of the enemy states to continue to make war. If a state can no longer produce airplanes and tanks, either because the factories have been destroyed or because there are no longer people to work in the factories, then its ability to resist is diminished.

Given the level of technology and development in WWII, strategic bombing had a chance at achieving military objectives, because the conflict was to carry on for multiple years. On the timescale of years, a country’s capacity to build armaments and resupply armies in the field can be crucial to victory.

Nuclear war changes this calculus. In a modern nuclear war involving SLBMs (Submarine launched ballistic missiles), ICBMs (Intercontinental ballistic missiles), strategic bombers, and other weapon systems, the majority of an adversary’s military, industrial and population centers could be destroyed in a matter of days or hours. It is hard to imagine a nuclear war lasting years or even months. Without a prolonged war, the original rationale for strategic bombing disappears, or is at least much reduced. A state may still wish to reduce the capacity of its enemy to fight future wars, but it can no longer claim that the wholesale destruction of cities is necessary to achieve military objectives in the current war.

Why then, did early US nuclear policies call for the destruction of cities?

Nuclear game theory in the 1960s

The destruction of cities was primarily a threat of inflicting harm rather than an attempt to destroy the capacity of the enemy to wage war. The idea, formalized by RAND game theorist Thomas Schelling, was that both the United States and the Soviet Union would threaten massive retaliation against each other’s civilian populations and industry to deter the other from starting a war.

Schelling developed a category of game theory that involved what he termed “mixed motive games”. Games where both sides sought advantage, but where the payoff to one side did not strictly correlate to the loss to the other side. In these types of games, both players may wish to avoid outcomes that are mutually unfavorable (Strategy of Conflict, pg. 89). In the case of nuclear deterrence, both sides strongly preferred to avoid nuclear war, and thus were both were deterred from taking actions that would directly lead to nuclear war.

Much of Schelling’s work concerns itself with how states in a nuclear stalemate can pursue their own advantage while avoiding escalation to nuclear war. In this type of game, states try to maneuver each other into positions where the only possible actions are 1) escalate and risk nuclear war or 2) de-escalate and concede something to the other side.

During the Cuban Missile Crisis, Kennedy ordered a blockade of Cuba, believing that such an action would not be sufficient for the Soviet Union to initiate a war. The United States believed that the Soviet Union would not try to break the blockade, because such an action would be recognized by both sides as starting a (nuclear) war. Because Kennedy proved correct in his belief that the Soviet Union would not go to war over the blockade nor risk initiating war by breaking the blockade, the United States used to its advantage both countries unwillingness to go to war.

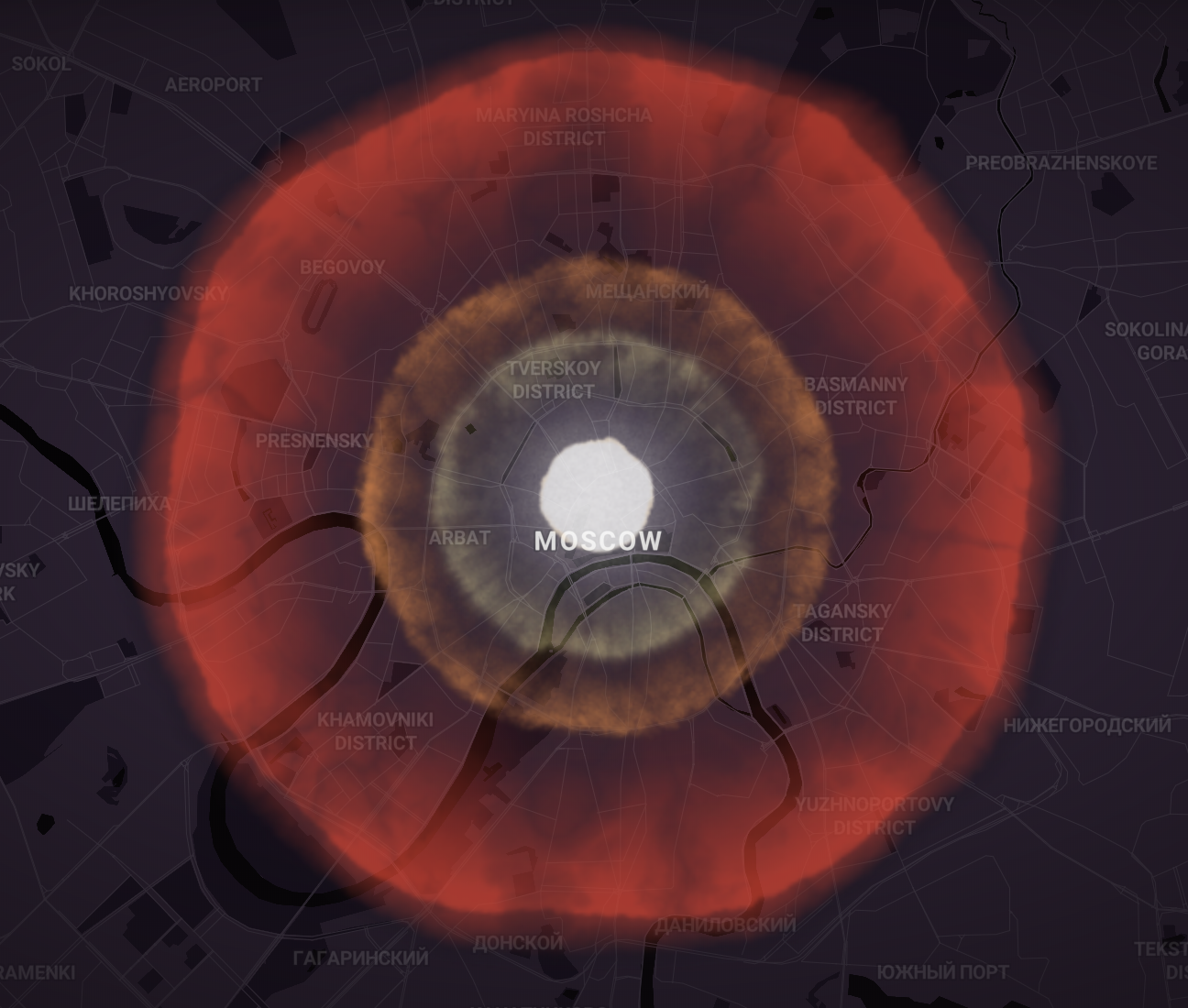

What does this have to do with the targeting cities? To answer this question it’s necessary to consider how a nuclear war might start. Although nuclear powers would almost always prefer to avoid a nuclear war, each has an incentive to strike first if they believe nuclear war to be inevitable. By striking first they may destroy their adversary’s nuclear forces before they can be used. At this point, it’s useful to define a couple of terms. Counterforce targeting refers to the targeting of enemy military installations, especially other nuclear forces. Countervalue targeting refers to the targeting of enemy infrastructure and population centers.

Consider the primary goal of a first strike. Under the most plausible nuclear war scenarios, it is to eliminate the nuclear forces of the rival state; its objective is primarily counterforce in nature. This is markedly different than the goal of a second strike. The primary goal of a second strike, under normal assumptions of deterrence, is actually to provide fulfilment of the pre-commitment made to retaliate if ever attacked. That is, it is necessary to actually be committed to attacking second so as to avoid being attacked in the first place.

Schelling effectively argued that the more punishing the second strike threatened to be, the more effective the deterrent would be also. If true, then in the event of a nuclear war, a state following the optimal strategy of deterrence would target cities as well as nuclear targets to make their nuclear response as punishing as possible; that is, it would destroy both counterforce and countervalue targets. This would seem to lead to a policy for states to attack cities, without a second thought. Indeed, this was the policy of the US and the Soviet Union in the 1950s and early 1960s. However, just because targeting cities promised to be a more effective deterrent did not mean it promised to be the best policy.

Given some probability of nuclear war, the effectiveness of a deterrent strategy ought to be weighed against the severity of the resulting war were that strategy employed. In other words, it might make sense for a state to commit to not targeting cities in a second strike if they themselves do not have their cities destroyed in a first strike. While this may reduce the effectiveness of their deterrent (and perhaps only marginally – nuclear war is plenty damaging without cities being destroyed – the fallout alone will kill many millions), it may also greatly reduce the severeness of a nuclear war.

Herman Kahn, a prominent and controversial RAND researcher, argued that states would be rational to refrain from destroying cities in a first strike, to retain some bartering power that might allow them to save more of their own cities. The argument is that the defending force might refrain from destroying many enemy cities if doing so prevented their own cities from being destroyed.

Kahn believed that the US should study and prepare for negotiating for the avoidance of US cities in a nuclear war and that in order to do this the country should:

- Develop the ability to have sufficiently protected or hidden nuclear forces to be able to both survive a first strike and carry out counterforce and countervalue attacks.

- Have “backup presidents”, or people with authority to both order attacks and negotiate with the Soviet Union in the midst of a war, and that the US should have multiple secure locations which are staffed 24/7 by these leaders.

Both Herman Kahn and Thomas Schelling agreed that negotiating the end of a nuclear war would be difficult, but both believed it was critical that nuclear states remain capable of negotiation. Schelling writes about this in his 1966 work, Arms and Influence:

The closing stage, furthermore, might have to begin quickly, possibly before the first volley had reached its targets; and even the most confident victor would need to induce his enemy to avoid a final, futile orgy of hopeless revenge. In earlier times, one could plan the opening moves of war in detail and hope to improvise plans for its closure; for thermonuclear war, any preparations for closure would have to be made before the war starts. … A critical choice in the process of bringing a war to a successful close–or to the least disastrous close–is whether to destroy or to preserve the opposing government and its principal channels of command and communication. If we manage to destroy the opposing government’s control over its own armed forces, we may reduce their military effectiveness. At the same time, if we destroy the enemy government’s authority over its armed forces, we may preclude anyone’s ability to stop the war, to surrender, to negotiate an armistice, or to dismantle the enemy’s weapons.*

Historical developments in US nuclear targeting policy

The United State’s nuclear targeting policy has evolved from one of indiscriminate destruction of military and civilian targets, including cities, to one that promises proportional retaliation. While the public documents, perhaps intentionally, do not make the US’s position clear, their implication is that the United States would only target cities in the event that their own cities were destroyed. The first nuclear targeting plans existed in the form of SIOP (Single Integrated Operational Plan). This classified document outlined our nuclear policy starting in 1961 until 2004, and now exists in the form of the Operations Plan (OPLAN). The first SIOP specified all out targeting of both military targets and population centers, that is both counterforce and countervalue targeting, in both first strike and second strike scenarios. Later SIOPs contained multiple options, including the option to hold the bombing of cities in reserve.

This paper: “The Trump Administration’s Nuclear Posture Review (NPR): In Historical Perspective” summarizes how the Kennedy administration began to advocate for a limited war scenario that spared cities:

President Kennedy went so far as to endorse Secretary of Defense McNamara’s effort to get the Soviets to agree to a “no cities” nuclear targeting rule, which McNamara and the President soon abandoned in the face of objections from NATO and the US Congress as well as the Kremlin that the idea was totally unrealistic. McNamara thereupon did a 180°turn to champion a MAD arms limitation (and retention) pact with the Soviets – to prevent nuclear war by guaranteeing it will be mutually suicidal. The Johnson administration’s effort to negotiate such a treaty with Kosygin was aborted in 1968 by the Soviet Union’s brutal repression of the reformist Dubcek regime in Czechoslovakia. McNamara continued to work secretly with the military, however, to enlarge the menu in the SIOP (Single Integrated Operational Plan) from which the president could select limited and controlled nuclear responses to a nuclear attack – preserving some possibility of a nuclear cease fire prior to Armageddon.*

Even though McNamara’s efforts to change nuclear war plans to spare cities failed, his influence led to changes in the SIOP that for the first time specified a flexible response in nuclear war planning. Nixon would later make additional changes to the SIOP, giving the United States even more flexibility in nuclear targeting scenarios. It is not clear whether the United States ever developed a serious “no cities” strategy during the Cold War, but it did at least lay the foundations for one.

For the first time in US history, President Obama’s administration stated the US would not target cities with nuclear weapons. However, this statement did not rule out escalation to countervalue targeting in the midst of a nuclear war, and is best interpreted to mean that the US would only target cities as a retaliatory measure. From the same Historical Perspective paper:

Yet Obama, while conceding to this presumed need to be prepared to actually use nuclear weapons in extreme situations, was not about to totally devolve the planning for such use onto the Pentagon…. he was adamant in his guidance to the military that if that crucial threshold ever had to be crossed, all operations had to be “consistent the fundamental principles of the Law of Armed Conflict. Accordingly, plans will … apply the principles of distinction and proportionality and seek to minimize collateral damage to civilian populations and civilian objects. The United States will not intentionally target civilian populations or civilian objects”(US Department of Defense, 2013 US Department of Defense. 2013. Report on Nuclear Employment Strategy of the United States Specified in Section 491 of 10 U.S.C. June 12.

The restrictive rules of nuclear engagement were translated into the military’s doctrinal language: “The new guidance,” elaborated the Pentagon’s June 2013 Report on Nuclear Employment Strategy, requires the United States to maintain significant counterforce capabilities [jargon for directed at strategic weapon systems] against potential adversaries. The new guidance does not rely on a ‘counter-value’ or ‘minimum deterrence’ strategy [jargon for directed at centers of population]. (US Department of Defense, 2013 US Department of Defense. 2013. Report on Nuclear Employment Strategy of the United States Specified in Section 491 of 10 U.S.C. June 12.

Did this mean that the United States was discarding its ultimate assured destruction threat for deterring nuclear war? Clearly not. The guidance was carefully drafted. Does not rely on is different from will not resort to. But more explicitly and openly than previously, the language indicates that assured massive destruction of the enemy country would be the very last resort in an already massively escalating nuclear war, in which all the lesser options had been exhausted and had failed to control the violence.

President Trump’s nuclear policy, as contained in the 2018 Nuclear Posture Review, differs in a number of ways from President Obama’s policies, but doesn’t substantially change the doctrine of holding the targeting of cities in reserve.

If deterrence fails, the initiation and conduct of nuclear operations would adhere to the law of armed conflict and the Uniform Code of Military Justice. The United States will strive to end any conflict and restore deterrence at the lowest level of damage possible for the United States, allies, and partners, and minimize civilian damage to the extent possible consistent with achieving objectives.

Every U.S. administration over the past six decades has called for flexible and limited U.S. nuclear response options, in part to support the goal of reestablishing deterrence following its possible failure. This is not because reestablishing deterrence is certain, but because it may be achievable in some cases and contribute to limiting damage, to the extent feasible, to the United States, allies, and partners.

Conclusion and takeaways:

The US nuclear targeting policy, in so much as public statements and documents reveal, has shifted substantially from a policy of targeting cities by default to a policy that leaves cities as reserve targets for full escalation scenarios. The US policy has never ruled out the possibility of escalation to full countervalue targeting and is unlikely to do so.

The maxim “no plan survives contact with the enemy” is especially worrying from the perspective of nuclear war planning. During the early cold war years described in Daniel Ellsberg’s book, the military culture promoted a dedication to nuclear readiness–so much so that officers violated their own protocols to ensure they could launch nuclear weapons in a crisis. Readiness for retaliation, especially full countervalue retaliation, naturally trades off against risk of full escalation.

As both Herman Kahn and Thomas Schelling made clear, communication between legitimate authorities is essential to the ability to negotiate the end of a nuclear conflict. Yet the military value of disabling an enemy’s nuclear command, control, and communications (NC3) capabilities is large. This may be the biggest risk to cities; if Moscow and Washington are both destroyed in the early stages of nuclear conflict, then this could easily escalate to all out countervalue targeting. It is important not only that some command structure with the authority to negotiate remain intact on each side, but also that both parties can communicate with each other and trust that the adversary’s command structure is actually intact and capable of negotiation.

Finally, all of this means very little if either of two potential adversaries fail to make plans for a) refraining from initial targeting of cities b) maintaining NC3 capabilities through an initial nuclear strike, and c) have the authority and intention to negotiate a peace & de-escalation. Indeed, public statements by Soviet leadership during the cold war suggested they had no intention of sparing cities in a retaliatory strike, making any possible US policy of gradual escalation potentially useless. Ultimately, it’s important to recognize here that not all nuclear war scenarios have equal outcomes, and that both sides in a nuclear conflict could benefit greatly from engaging in strategic restraint.